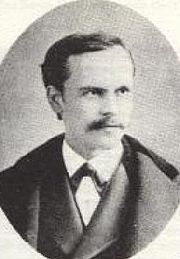

Benjamin Tucker

Benjamin Ricketson Tucker (April 17, 1854 – June 22, 1939) was a proponent, in the 19th century, of American individualist anarchism, which he called "unterrified Jeffersonianism,"[1] and editor and publisher of the individualist anarchist periodical Liberty.

Contents

Early life and influences

Tucker was born on April 17, 1854, in South Dartmouth, Massachusetts. In 1872, while a student at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Tucker attended a convention of the New England Labor Reform League in Boston, chaired by William B. Greene, author of Mutual Banking (1850). At the convention, Tucker purchased Mutual Banking, True Civilization, and a set of Ezra Heywood's pamphlets. Furthermore, (Free-love anarchist) Ezra Heywood introduced Tucker to William B. Greene and Josiah Warren, author of True Civilization (1869). He also started a relationship with Victoria Woodhull, which lasted for 3 years.

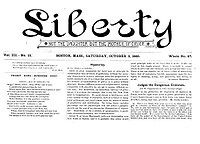

Tucker made his debut in liberty-minded circles 1876, when Heywood published Tucker's first ever English translation of Proudhon's classic work What is Property?. In 1877–1878, Tucker published his original journal, Radical Review, which ran for only four issues. From August 1881 to April 1908, he published the periodical, Liberty, "widely considered to be the finest individualist-anarchist periodical ever issued in the English language".[2] In 1892, he moved the Liberty from Boston to New York.

Anarchism

Template:Anarchism sidebar Tucker said that he became an anarchist at the age of 18.[3] Tucker's contribution to American individualist anarchism was as much through his publishing as his own writing. Tucker was also the first to translate into English Max Stirner's The Ego and Its Own – which Tucker claimed was his proudest accomplishment. Tucker also translated Mikhail Bakunin's book God and the State.[4] In the anarchist periodical Liberty, he published the original work of Stephen Pearl Andrews, Joshua K. Ingalls, Lysander Spooner, Auberon Herbert, Victor Yarros, and Lillian Harman, daughter of the free love anarchist Moses Harman, as well as his own writing.

He also published George Bernard Shaw's first original article to appear in the United States, and the first American translated excerpts of Friedrich Nietzsche. In Liberty, Tucker both filtered and integrated the theories of such European thinkers as Herbert Spencer and Pierre-Joseph Proudhon, the economic and legal theories of the American individualists Lysander Spooner, William B. Greene and Josiah Warren, and the writings of the free thought and free love movements in opposition to religiously based legislation and prohibitions on non-invasiveTemplate:Clarify behavior. Through these influences Tucker produced a rigorous system of philosophical or individualist anarchism that he called Anarchistic-Socialism,[5] arguing that "[the] most perfect Socialism is possible only on the condition of the most perfect individualism."[6]

According to Frank Brooks, an historian of American individualist anarchism, it is easy to misunderstand Tucker's claim to "socialism". Before Marxists established a hegemony over definitions of socialism, "the term socialism was a broad concept." Tucker, as well as most of the writers and readers of Liberty, understood "socialism" to refer to one or more of various theories aimed at solving "the labor problem" through radical changes in the capitalist economy. Descriptions of 'the problem', explanations of it causes, and proposed solutions (for example, abolition of private property, cooperatives, state-ownership, and so on) varied among "socialist" philosophies.[7]

Tucker said socialism was the claim that "labor should be put in possession of its own,"[8] holding that what "state socialism" and "anarchistic socialism" had in common was the labor theory of value.[9] However, "Instead of asserting, as did socialist anarchists, that common ownership was the key to eroding differences of economic power," and appealing to social solidarity, Tucker's individualist anarchism advocated distribution of property in an undistorted natural market, as a mediator of egoistic impulses and a source of social stability.[10]

Tucker said, Template:Quote

Tucker first favored a natural rights philosophy, in which an individual had a right to own the fruits of his labor; then he abandoned it in favor of "egoism" (influenced by Max Stirner), in which he believed that only the "right of might" exists, until overridden by contract.

He objected to all forms of communism, believing that even a stateless communist society must encroach upon the liberty of individuals.[11] Template:Quote

Tucker connected his economic views in the following form with those of Pierre Joseph Proudhon, Josiah Warren and Karl Marx in the following form:

Liberty (1881–1908)

Liberty was a nineteenth-century anarchist periodical published in the United States by Benjamin Tucker, from August 1881 to April 1908. The periodical was instrumental in developing and formalizing the individualist anarchist philosophy through publishing essays and serving as a format for debate. Contributors included Benjamin Tucker, Lysander Spooner, Auberon Herbert, Dyer Lum, Joshua K. Ingalls, John Henry Mackay, Victor Yarros, Wordsworth Donisthorpe, James L. Walker, J. William Lloyd, Florence Finch Kelly, Voltairine de Cleyre, Steven T. Byington, John Beverley Robinson, Jo Labadie, Lillian Harman, and Henry Appleton. Included in its masthead is a quote from Pierre Proudhon saying that liberty is "Not the Daughter But the Mother of Order."The Four Monopolies

Template:Libertarian socialism Template:American socialism Tucker argued that the poor condition of American workers resulted from four legal monopolies based in authority:

His focus, for several decades, became the state's economic control of how trade could take place, and what currency counted as legitimate. He saw interest and profit as a form of exploitation, made possible by the banking monopoly, which was in turn maintained through coercion and invasion. Tucker called any such interest and profit "usury" and he saw it as the basis of the oppression of the workers. In his words, Template:Quote

Tucker believed that usury was immoral; however, he upheld the right of all people to engage in immoral contracts. Template:Quote

He asserted that anarchism is meaningless Template:Quote

Land monopoly

He acknowledged that "anything is a product upon which human labor has been expended," but would not recognize full property rights to labored-upon land: Template:Quote

Tucker opposed granting title to land that was not in use; he argued that an individual should use land continually, in order to retain exclusive right to it. He believed that if this practice were not followed, there was a 'land monopoly'.

Money and banking monopoly

Tucker also opposed state protection of the 'banking monopoly' – the requirement that one must obtain a charter to engage in the business of banking. He hoped to raise wages by deregulating the banking industry, reasoning that competition in banking would drive down interest rates and stimulate enterprise. Tucker believed this would decrease the proportion of individuals seeking employment, and wages would be driven up by competing employers. "Thus, the same blow that strikes interest down will send wages up."[12]

He did not oppose individuals being employed by others, but due to his interpretation of the labor theory of value, he believed that in the present economy individuals do not receive a wage that fully compensates them for their labor. He wrote that, if the four "monopolies" were ended, Template:Quote

Tariffs and patents

Tucker opposed protectionism, believing that tariffs caused high prices, by preventing national producers from having to compete with foreign competitors. He believed that free trade would help keep prices low and therefore would assist laborers in receiving their "natural wage". Tucker did not believe in intellectual property rights in the form of patents, on the grounds that patents and copyrights protect something which cannot rightfully be held as property. He wrote that the basis for property is "the fact that it is impossible in the nature of things for concrete objects to be used in different places at the same time."[13] Property in concrete things is "socially necessary": Template:Quote

Because ideas are not concrete things, they should not be held and protected as property. Ideas can be used in different places at the same time, and so their use should not be restricted by patents.[14] This was a source of conflict with the philosophy of fellow individualist Lysander Spooner, who saw ideas as the product of "intellectual labor" and therefore private property.[15]

Yarros

According to Victor Yarros: Template:Quote

Attitude to unions

Tucker rejected the legislative programs of labor unions, laws imposing a short day, minimum wage laws, forcing businesses to provide insurance to employees, and compulsory pension systems.[16] He believed instead that strikes should be organized by free workers rather than by bureaucratic union officials and organizations. He argued, Template:Quote

and furthermore, Template:Quote

Anarchist society

Tucker envisioned an individualist anarchist society as Template:Quote

rather than a bureaucratic organization of workers organized into rank and file unions. However, he did hold a genuine appreciation for labor unions (which he called "trades-union socialism"), and saw it as "an intelligent and self-governing socialism" saying, "[they] promise the coming substitution of industrial socialism for usurping legislative mobism."[17]

Carson's critique

Tucker's concept of the four monopolies has been discussed by Kevin Carson in his book Studies in Mutualist Political Economy. Carson incorporates the idea into his thesis that the exploitation of labor is only possible due to state intervention. However, he argues that Tucker failed to notice a fifth form of privilege: transportation subsidies. Template:Quote

Carson believes that Tucker's four monopolies, and transportation subsidies, created the foundation for the monopoly capitalism and military-industrial complex of the 20th century.[18] Ironically, Carson has also noted that the heavy use of this new monopoly by the state may be grounds for optimism that Tucker was unaware of. As, in order to maintain the corporate system, the state has been forced to continually ratchet up the level of subsidies that it provides until it is very close to bankruptcy.

Private defense forces

Tucker did not have a utopian vision of anarchy, where individuals would not coerce others.[16] He advocated that liberty and property be defended by private institutions. Opposing the monopoly of the state in providing security, he advocated a free market of competing defense providers, saying "defense is a service like any other service; ... it is labor both useful and desired, and therefore an economic commodity, subject to the law of supply and demand."[19]

He said that anarchism "does not exclude prisons, officials, military, or other symbols of force. It merely demands that non-invasive men shall not be made the victims of such force. Anarchism is not the reign of love, but the reign of justice. It does not signify the abolition of force-symbols but the application of force to real invaders."[20] Tucker expressed that the market-based providers of security would offer protection of land that was being used, and would not offer assistance to those attempting to collect rent: Template:Quote

Embrace of "egoism"

Template:Individualism sidebar Tucker abandoned natural rights positions and converted to Max Stirner's Egoist anarchism. Rejecting the idea of moral rights, Tucker said that there were only two rights, "the right of might" and "the right of contract." He also said, after converting to Egoist individualism, "In times past...it was my habit to talk glibly of the right of man to land. It was a bad habit, and I long ago sloughed it off....Man's only right to land is his might over it."[21] In adopting Stirnerite egoism (1886), Tucker rejected natural rights which had long been considered the foundation of libertarianism. This rejection galvanized the movement into fierce debates, with the natural rights proponents accusing the egoists of destroying libertarianism itself. So bitter was the conflict that a number of natural rights proponents withdrew from the pages of Liberty in protest even though they had hitherto been among its frequent contributors. Thereafter, Liberty championed egoism although its general content did not change significantly."[22] This led to a split in American Individualism between the growing number of Egoists and the contemporary Spoonerian "Natural Lawyers". Tucker came to hold the position that no rights exist until they are created by contract. This led him to controversial positions such as claiming that infants had no rights and were the property of their parents, because they did not have the ability to contract. He said that a person, who physically tries to stop a mother from throwing her "baby into the fire", should be punished for violating her property rights. He said that children would shed their status as property, when they became old enough to contract "to buy or sell a house" for example, noting that the precocity varies by age and would be determined by a jury in the case of a complaint.[23]

He also came to believe that aggression towards others was justifiable if doing so led to a greater decrease in "aggregate pain" than refraining from doing so. He said:

Tucker now said that there were only two rights, "the right of might" and "the right of contract." He also said, after converting to Egoist individualism, that ownership in land is legitimately transferred through force unless contracted otherwise. In 1892, he said "In times past...it was my habit to talk glibly of the right of man to land. It was a bad habit, and I long ago sloughed it off. Man's only right to land is his might over it. If his neighbor is mightier than he and takes the land from him, then the land is his neighbor's, until the latter is dispossessed by one mightier still."[24]

However, he said he believed that individuals would come to the realization that "equal liberty" and "occupancy and use" doctrines were "generally trustworthy guiding principle of action," and, as a result, they would likely find it in their interests to contract with each other to refrain from infringing upon equal liberty and from protecting land that was not in use.[25] Though he believed that non-invasion, and "occupancy and use as the title to land" were general rules that people would find in their own interests to create through contract, he said that these rules "must be sometimes trodden underfoot."[26]

Several periodicals "were undoubtedly influenced by Liberty's presentation of egoism. They included: I published by C.L. Swartz, edited by W.E. Gordak and J.W. Lloyd (all associates of Liberty); The Ego and The Egoist, both of which were edited by Edward H. Fulton. Among the egoist papers that Tucker followed were the German Der Eigene, edited by Adolf Brand, and The Eagle and The Serpent, issued from London. The latter, the most prominent English-language egoist journal, was published from 1898 to 1900 with the subtitle 'A Journal of Egoistic Philosophy and SociologyTemplate:'".[27]

Late life

In 1906, he opened Tucker's Unique Book Shop in New York City – promoting "Egoism in Philosophy, Anarchism in Politics, Iconoclasm in Art". In 1908, a fire destroyed Tucker's uninsured printing equipment and his 30-year stock of books and pamphlets. Tucker's lover, Pearl Johnson – 25 years his junior – was pregnant with their daughter, Oriole Tucker. Six weeks after Oriole's birth, Tucker closed both Liberty and the book shop and retired with his family to France. In 1913, he came out of retirement for two years to contribute articles and letters to The New Freewoman which he called "the most important publication in existence."

Later Tucker became much more pessimistic about the prospects for anarchism. In 1926, Vanguard Press published a selection of his writings entitled Individual Liberty, in which Tucker added a postscript[28] to "State Socialism and Anarchism",[29] which stated Template:Quote

But, Tucker argued, Template:Quote

By 1930, Tucker had concluded that centralization and advancing technology had doomed both anarchy and civilization. Template:Quote

According to James Martin, when referring to the world scene of the mid-1930s in private correspondence, Tucker wrote: "Capitalism is at least tolerable, which cannot be said of Socialism or Communism" and went on to observe that, "under any of these regimes a sufficiently shrewd man can feather his nest.".[30]

Susan Love Brown claims that this unpublished, private letter, which does not distinguish between the anarchist socialism Tucker advocated and the state socialism he criticized, served in "providing the shift further illuminated in the 1970s by anarcho-capitalists."[31]

Tucker died in Monaco in 1939, in the company of his family. His daughter, Oriole, reported, "Father's attitude towards communism never changed one whit, nor about religion.... In his last months he called in the French housekeeper. 'I want her,' he said, 'to be a witness that on my death bed I'm not recanting. I do not believe in God!"[32]

In Popular Culture

In the alternate history novel The Probability Broach by L. Neil Smith as part of the North American Confederacy Series, in which the United States becomes a Libertarian state after a successful Whiskey Rebellion and the overthrowing and execution of George Washington by firing squad for treason in 1794, Benjamin Tucker served as the 17th President of the North American Confederacy from 1892 to 1912.

References

- ↑ McCarthy, Daniel (2010-01-01) A Fistful of Dynamite, The American Conservative

- ↑ {{#invoke:Citation/CS1|citation |CitationClass=journal }}

- ↑ Symes, Lillian and Clement, Travers. Rebel America: The Story of Social Revolt in the United States. Harper & Brothers Publishers. 1934. p. 156

- ↑ at marxists.org

- ↑ "The economic principles of Modern Socialism are a logical deduction from the principle laid down by Adam Smith in the early chapters of his “Wealth of Nations,” – namely, that labor is the true measure of price...Half a century or more after Smith enunciated the principle above stated, Socialism picked it up where he had dropped it, and in following it to its logical conclusions, made it the basis of a new economic philosophy...This seems to have been done independently by three different men, of three different nationalities, in three different languages: Josiah Warren, an American; Pierre J. Proudhon, a Frenchman; Karl Marx, a German Jew...That the work of this interesting trio should have been done so nearly simultaneously would seem to indicate that Socialism was in the air, and that the time was ripe and the conditions favorable for the appearance of this new school of thought...So far as priority of time is concerned, the credit seems to belong to Warren, the American, – a fact which should be noted by the stump orators who are so fond of declaiming against Socialism as an imported article." Benjamin Tucker. Individual Liberty

- ↑ cited by Peter Marshall, Demanding the Impossible, p. 390

- ↑ Brooks, Frank H. 1994. The Individualist Anarchists: An Anthology of Liberty (1881–1908). Transaction Publishers. p. 75.

- ↑ Tucker, Benjamin. "State Socialism and Anarchism," ¶ 1.

- ↑ Brown, Susan Love. 1997. "The Free Market as Salvation from Government". In Meanings of the Market: The Free Market in Western Culture. Berg Publishers. p. 107.

- ↑ Freeden, Michael. 1996. Ideologies and Political Theory: A Conceptual Approach. Oxford University Press. p. 276.

- ↑ Madison, Charles A. Anarchism in the United States. Journal of the History of Ideas, Vol 6, No 1, January 1945, p. 53.

- ↑ [1] Libertarian Heritage No. 23. Template:ISSN ISBN 1-85637-549-8, Libertarian Alliance, 2002.

- ↑ "The Attitude of Anarchism toward Industrial Combinations"

- ↑ Tucker, Benjamin: The Attitude of Anarchism toward Industrial Combinations

- ↑ Spooner, Lysander. The Law of Intellectual Property: or an essay on the right of authors and inventors to a perpetual property in their ideas., Chapter 1, Section VI.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 {{#invoke:Citation/CS1|citation |CitationClass=journal }}

- ↑ The Individualist Anarchists, pp. 283–284

- ↑ Kevin Carson. Studies in Mutualist Political Economy, Ch. 5

- ↑ "On Picket Duty." Liberty. July 30, 1887; 4, 26. p4.

- ↑ Tucker, Benjamin. Liberty October 19, 1891.

- ↑ Tucker, Instead of a Book, p. 350

- ↑ Wendy Mcelroy. "Benjamin Tucker, Individualism, & Liberty: Not the Daughter but the Mother of Order"

- ↑ McElroy, Wendy. 2003. The Debates of Liberty. Lexington Books. pp. 77–79

- ↑ Benjamin R. Tucker, "Response to 'Rights,' by William Hansen," Liberty, December 31, 1892; 9, 18; p. 1

- ↑ Benjamin R. Tucker, "The Two Conceptions of Equal Freedom," Liberty, April 6, 1895; 10, 24; p. 4

- ↑ Tucker, "Land Tenure Again"

- ↑ McElroy, Wendy. A Reconsideration of Trial by Jury, Forumulations, Winter 1998–1999, Free Nation Foundation

- ↑ a postscript

- ↑ "State Socialism and Anarchism"

- ↑ James J. Martin, Men Against the State, 1970:275, quoting from the Baskette Collection (1933–1935)

- ↑ Brown, Susan L., The Free Market as Salvation from Government, Meanings of the Market: The Free Market in Western Culture, p. 108

- ↑ Template:Cite book

Further reading

External links

{{#invoke:Side box|main}} {{#invoke:Side box|main}} Template:Wikisource author

- Instead of a Book, by a Man Too Busy to Write One (1893, 1897)

- Travelling in Liberty: a complete online archive of Tucker's journal Liberty (1881–1908)

- Several works by Tucker at Anarchy Archives

- State Socialism and Anarchism. How far they agree and wherein they differ (1886)

- Liberty and Taxation From the magazine Liberty 1881–1908

- Individual Liberty (1926); collection of articles

- Tucker on Property, Communism and Socialism

- BlackCrayon.com: People: Benjamin Tucker

- Benjamin Tucker Anarchy Archives

- Benjamin Tucker, Liberty, and Individualist Anarchism by Wendy McElroy

- Benjamin Ricketson Tucker from "CLASSicalLiberalism" archive

- Benjamin Tucker and His Periodical, Liberty by Carl Watner

- Memories of Benjamin Tucker by J. William Lloyd (1935)

- An Interview With Oriole Tucker Tucker's daughter reveals biographical information, by Paul Avrich

- Benjamin R Tucker & the Champions of Liberty – A Centenary Anthology Edited by Michael E. Coughlin, Charles H. Hamilton and Mark A. Sullivan

- Template:Gutenberg author

- Template:Internet Archive author

- Template:Librivox author

- Template:FAG

- 1854 births

- 1939 deaths

- American anarchists

- American anti-communists

- Anarchist theorists

- American magazine editors

- American socialists

- American magazine publishers (people)

- American political philosophers

- American political writers

- American male writers

- American tax resisters

- Libertarian socialists

- American atheists

- Atheism activists

- Egoist anarchists

- Individualist anarchists

- Free-market anarchists

- Massachusetts Institute of Technology alumni

- Mutualists

- Free love advocates

- Left-libertarians